Technical deep-dive into the bouncing phenomenon plaguing 2022 Formula 1 cars, with proposed aerodynamic solutions.

Aerodynamics Solutions to Porpoising In 2022 Formula 1 Cars

The phenomenon causing 2022 F1 cars to bounce down the straights is known colloquially as "porpoising". Behind the scenes, teams of experienced aerodynamicists are working quickly to find solutions. Many have asked: how did they miss this issue?

With the growing accessibility of basic CFD aerodynamics simulation testing, more people are trying their hand at vehicle aerodynamic development; accordingly, this is an opportunity to discuss some of the critical points in aerodynamic design. The concepts involved are important both in and outside of Formula One. I hope this article will be of interest to those of you who are enjoying aero as a hobby and serve as an interesting read for those who follow it as a curiosity.

Historical Context

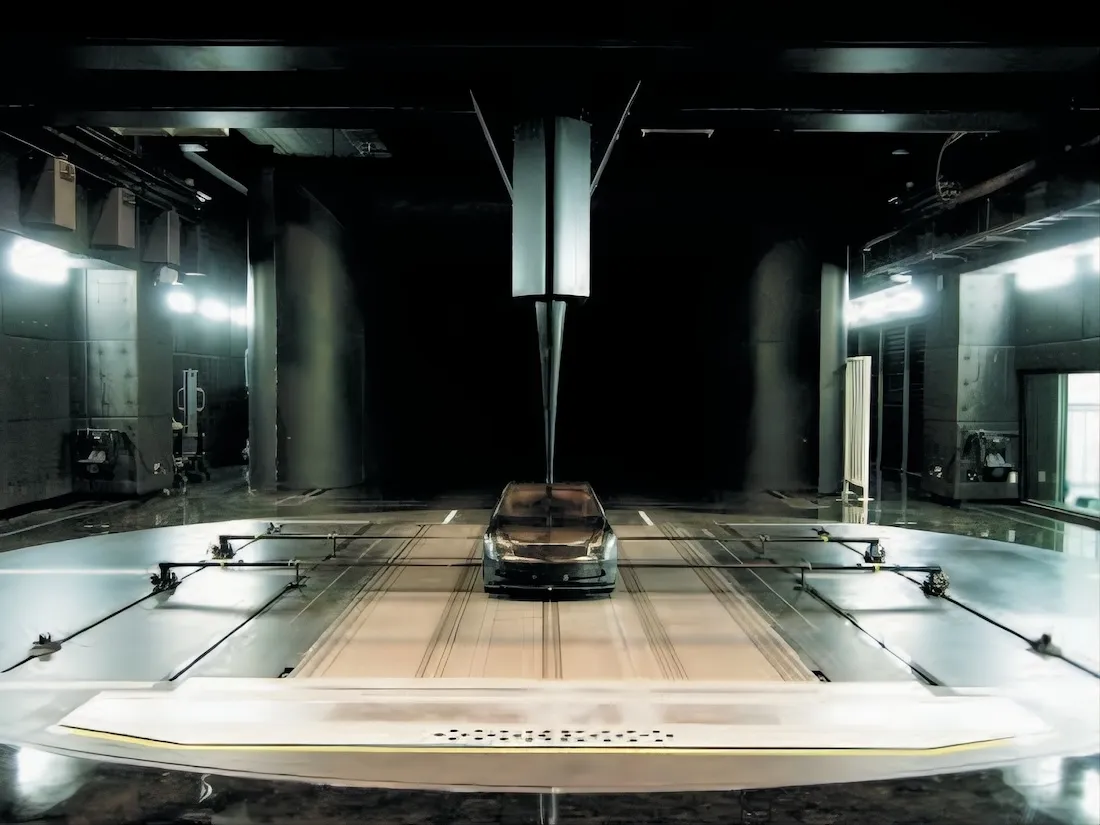

To introduce myself, I'm Andrew Brilliant, the director of AMB Aero, an aerodynamics consulting firm based in Sapporo, Japan. We utilize both in-house 40 DP-TFLOP super-compute CFD and physical wind tunnel test facilities. My mentor and partner Yoshi Suzuka was a major contributor to the modern understanding of underbody tunnels. His work shaped them from the early F1 style 'underbody wings' to what would later become known as the modern 'venturi' style during the development of Nissan GTP cars.

At AMB Aero, we have been fortunate enough to develop all sorts of cars – especially many race cars – all over the world. Thanks to classes like IndyCar, LMP, or even Hill Climb and Time Attack that never fell victim to the 'flat floor dark ages'. We have completed more than ten thousand CFD and wind tunnel tests for tunnel cars alone.

In the late 1970s Lotus first discovered this phenomenon when their wind tunnel model was not sufficiently rigid resulting in the side pods sagging closer to the ground. As they did, downforce increased sharply. Lotus engineers then sought to understand this phenomenon and in doing so determined to close the sides of the floor, leading to the now-famous 'sliding skirts' (that were subsequently banned).

So powerful was this ride height effect, that after banning skirts, a car was run with completely solid suspension. In this infamous test, the driver commented that the car was quicker set low and solid, but he struggled with vision and vibration. The driver asked for a padded seat and was jokingly suggested to sit on his wallet.

Understanding Ground Effect

The concept of designing-in ride height sensitivity became deeply rooted in modern racecar aerodynamics. Generally, cars are run close to the ground to maximize underbody downforce (among other reasons), and accordingly – much as Lotus found in the 70's – it is incumbent on designers to manage this ground effect phenomenon towards a net performance advantage.

In the early days, it was believed that the ground effect acted similarly to the known behavior of airplane wings wherein lift increases with proximity to the ground. Many years later, we would come to understand some differences with ground vehicles and that the proximity of underbody wing forms is not the major cause of extreme sensitivity to ride height.

At AMB Aero we call them underbody tunnels. In our experience at AMB, this sensitivity is primarily due to changing flow field resulting from the relative position between the tire and the sprung body of the car. In the case of Formula cars, this can be conceptualized as the position above vs below the floor.

Evolution of Tunnel Design

This early prototype imitated the simple "underwing" concept and eventually evolved into the shape of Yoshi Suzuka's Nissan P35 in the early 1990s.

This along with many aerodynamic improvements took thousands of wind tunnel tests. The downforce generated was elevated to the stuff of legend. The complexity of flows involved in F1 has grown ever more intricate.

As you can see above, the modern Formula 1 car tunnel is closer to a "Venturi" type, unlike those early 'wing style' F1 side pods.

Understanding Porpoising

Porpoising is bouncing or oscillation in front, rear, or both caused by a loss in downforce at some ride height resulting in downforce being lost. Once downforce is lost the suspension springs then return the car to a higher ride height, however in this position the flow field again generates additional downforce and restarts the cycle.

The term 'porpoising' came from the early designs where the front wing was extremely sensitive to pitch change; an appropriate change in rear ride height caused front downforce to increase subsequent to the rear rising. This back-to-front bouncing resembled a dolphin coming out of the water nose-up and dipping back under with the nose down over and over.

Aero Maps and Sensitivities

The real cause of porpoising is better described as what aerodynamicists term as a 'sensitivity'. There are lots of sensitivities and in this case, the relevant one is ride height, being the distance from an arbitrary point on the car to a point on the ground. One of the most basic tools we use is called an aero map, a graph visualizing an aerodynamic behavior of a car.

It is easy to see from a map like that just how irrelevant and limiting a single value for downforce or drag can be. Aside from the huge variance across speed ranges, you could pick a number for downforce at some ride height you would never see in a corner (where downforce is helping you go quicker) or at some wing angle that would make you under-steer straight off the track.

Asking the downforce of the car is like asking what is the altitude of Europe? Are you in the Swiss Alps or on a Mediterranean beach? The question needs important context for a correct and relevant answer.

Technical Solutions

A modern 'venturi' style tunnel can be imagined as three components: the volume reducing throat section, followed by the minimum diameter nozzle section, and lastly the expanding diffuser section. Porpoising likely begins late in the nozzle or diffuser where flow velocities are higher and adverse pressure gradients can easily lead to flows abruptly detaching from the diffuser wall.

On any car with aerodynamic downforce applied to a suspended mass (the tire's spring rate also being a form of suspension), the car will always find a state of equilibrium; the ride height will compress until springs support the aerodynamic forces. As speed increases, so does downforce – the ride height will decrease increasing downforce again.

Wind Tunnel Development

Formula 1 aerodynamicists are not the first to experience this phenomenon through F1 attracts so much more attention as early testing is very public. We have supported prototype and even Time Attack customers with similar issues through to resolution. It is definitely not uncommon, in most categories it can be avoided through the careful use of CFD and wind tunnel testing.

Admittedly it is a far more difficult problem in F1 given the complexities of vehicle forms and the performance margins sought. This said, given the number of skilled people and the quality of tools available I am confident the problem will be solved quickly. We may even see evolving solutions over the course of the season and clean slate solutions next year.

Safety Considerations

Tunnels are far safer than diffusers in this regard as flat floors suffer from much higher pitch sensitivity than tunnels. A tunnel car can see larger negative pitch angles before lift is achieved. From this perspective, a tunnel may even be considered a safety device when compared with a flat floor. It also offers a cleaner wake to promote exciting racing by lessening aerodynamic losses to the car following behind.

The porpoising seen this year is a relatively mild phenomenon resulting only in reduced lap time and (possibly) driver discomfort; drivers can simply reduce speed when it starts. The sudden behavior of something like a blow-over/vehicle flip will be completely unstoppable. Understanding has advanced much and problems like this have become increasingly rare and less severe.

Conclusion

Modern racecar aerodynamics –particularly in Formula 1– are complex systems; without looking in detail at CFD or wind tunnel data it would be impossible to definitively know the probable causes of a specific car. It could be that Ferrari's wide side pods help produce higher-energy and better-directed flow into the tunnel throat. Mercedes uses a narrow side pod, perhaps this leaves them heavily dependent on a rear beam wing being more vulnerable to rear ride height effects.

AMB Aero is a complete end-to-end design service with winning race and championship history at many levels of motorsport, all over the world. Comprehending aerodynamics is both an art and a science. Successfully employing engineered aero requires addressing specific challenges in all areas of the project while satisfying the customer's overall objectives and constraints.

Applied Dynamics Research

Applied Dynamics Research